‘Twas in a seaboard town, the week between Christmas and New Years, when the fabric of caring, courtesy and wellbeing, woven ever so slowly, in fits and starts, by the biological and social forces of the community within their shared origins and histories, both material and metaphysical, began to fray and be stripped by the wind which was blowing in from the sea, caused partially by an atmospheric river bomb cyclone once in a generation weather event. The signs of a coming turn for the worse had been there for quite some time, ignored or avoided by most of the populace. Generally, folks had come to not take importance any longer in the foretelling of the future, not thinking too much about what lay ahead and what kinds of flora would be sprouting from the seeds brought in by the leeward winds over many, many years. Suddenly, there it was, like a pileup on a freeway in a snow storm. One minute you are cruising along normally, cautious yet confident, and then before you can react, the wreckage looms right in the foreground as you yourself plow right in and add to it, as does the fellow behind you.

The milk had gone sour and the cheese was moldy, yet no one seemed to know why or could manage any ideas about what to do about it. Despite the massive precipitation, the air seemed dry and stale. The vegetables all wilted and water would no longer boil over a flame. The upholstery, fine yesterday, was soiled and torn. The animals roamed free and many of the stores were full of squirrels, wild turkeys and deer coming in through the automatic doors. No one could tell if it was day or night, as the sky was a perpetual dark gray, with a faint orange glow filling the atmosphere that came and went as it pleased. As it was the “holiday season”, all the festivities and planned parties took on a new tone of confusion and even animosity. Children were crying, as were many adults. Muttering and mumbling to oneself, or to no one in particular, had replaced the act of conversation, an interaction so foundational to personal and social relations, which itself had been becoming more and more questionably effective for quite some time.

A negating of roles and responsibilities was spreading like monkeypox. People refused, at first, to go to the holiday parties of their family or their employer. “I’d rather open a vein and bleed out than sit here and read this teleprompter one more goddamn day!” said the news anchor over the air on one of the town’s most popular television channels. “Me too! Me too!” the people screamed, and this viewpoint, this choice of opting out, in the strongest most possible terms, was seemingly accepted by one and all as the week went on.

Did you mail the Christmas cards? “I’d rather open a vein and bleed out right here!”

Did you feed the cat? “I’d rather open a vein!”

Are you going to Todd’s New Years party? “I’d rather open a vein!”

Are you coming right home after work? “I’d rather open a vein!”

On and on it went and no one could do anything about it, so they all joined in one by one, shouting and screaming when they weren’t mumbling and muttering to themselves. The rain came down in buckets, and as the air got a bit chillier and it turned into freezing rain, sleet as some people remember calling it back in olden times. The wind picked up and the falling water crystals formed into hard spiky little balls and soon it was hailing, seemingly for hours.

Bring the car into the garage. “I’d rather open a vein!”

Shovel the sidewalk before it gets too deep. “I’d rather open a vein!”

Take these books back to the library. “I’d rather open a vein!”

Get a fucking haircut, would you please? “I’d rather open a vein and bleed out right here!”

The hail turned to snow and then back to hail and then back to rain and sleet and the rivers overflowed, vehicles were abandoned and the wind blew the leaves and thinner branches into giant whirling airborne tumbleweeds, only much more dangerous, lethal they were, as big masses of decayed plant life zoomed through town like comets. People slouched low and hunkered indoors until they couldn’t take it anymore and went stumbling through the streets, drenched by the downpours, felled at times by the streaming leaf and twig comets, watched by the animals who laid down in the window sills of the buildings, staring out at the people and the goings-on.

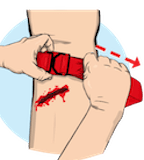

Just when a feeling of respite began to be felt, when a sense of decompression filled the air and gave people some hope, it would start back up again, the sense of doom constricting and tightening like a tourniquet around the arteries. Finally, the madness entered a new stage, and some people found whatever sharp object was nearby and began to, in actuality, open their veins, slicing and dicing their way up and down their arms and legs, on their necks and torsos. Most folks were too sloppy and unprepared for such a task to do any real harm to themselves. Their minds had been worn down and dulled like the blades of the ice scrapers and grilling tools that they grabbed and crisscrossed across their bodies with reckless abandon. Many of the self-flagellators ended up appearing as if they’d been bitten and scratched by a playfully aggressive cat, but nothing worse than that.

It was all too much, too much. Nothing was important anymore, or everything was too important. Nobody could tell which, if there was a difference between the two to be noticed at all. A man walked solemnly through the town, in a long, elegant raincoat and a beautiful crimson umbrella. Or perhaps it was a woman? No one observing this person was too sure and if the animal onlookers could detect a gender, or even cared at all to notice such a thing, they were not letting on. As this person, this being, walked down the road, some even claim to have seen the body floating in the air, being conducted along as if on an invisible conveyor belt or perhaps suspended by wires hung down from the sky, a calming effect emanated from the wake of the interloper, wafting out like the wake of a rowboat on a placid lake. The air lightened a bit and the hail grew smaller in size. The chilliness went out of the air and the wild turkeys and such began exiting the commercial buildings downtown. A silence fell upon the land.

Things did not go back to normal, not at all. They had been irrevocably changed. How so? For better or for worse? No one could decide for sure. Things were just different that’s all, and it took quite a bit of time for people to adjust to this new reality. There was relief and even hope in the air, but most people still carried around quite a bit of pain inside of them. It was emotional and spiritual pain, a loss, and for some it was even manifested physically, a near-constant tightening of the abdomen or an aching in the chest that never went away. That’s just how people had to live from that point forward, and they did. They adjusted and they kept on.